ARTWORK

Marilyn Minter

Drip Drop, 2018

Chromogenic print

© Marilyn Minter

Bert Stern

Marilyn, Double X, 1962

Ektacolor print

© Estate of Bert Stern

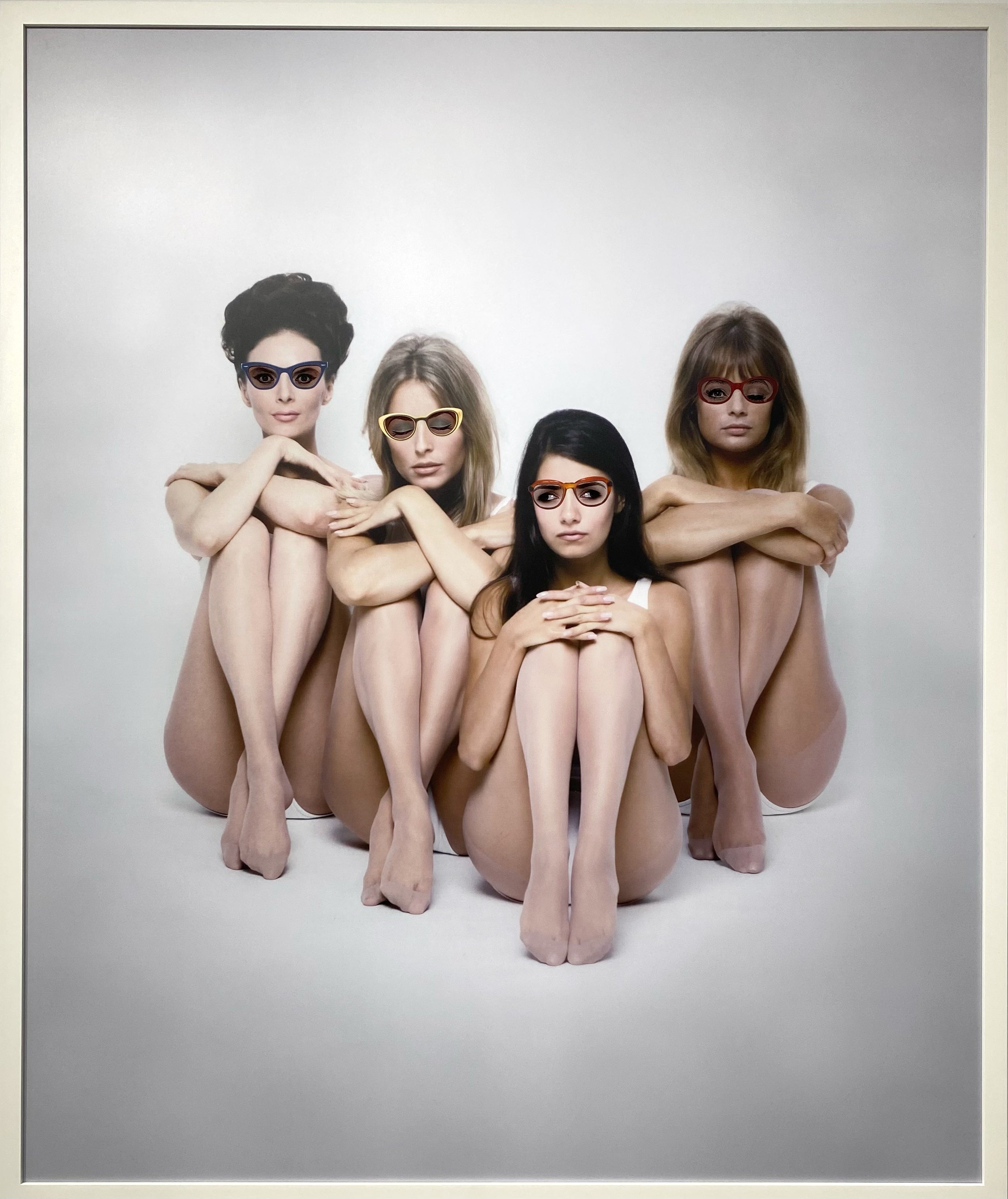

Daniel Cherbuin

Tetrapak, 2022

Print on dibond, LCD screen, wooden frame

© Daniel Cherbuin

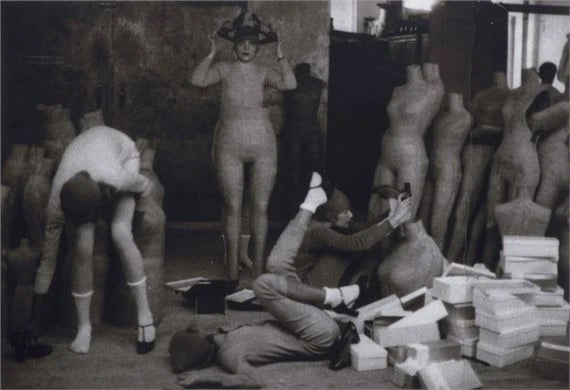

Deborah Turbeville

For Charles Jourdan: Candy Pratt, Betsey Johnson, Tia, Beverly Morgan, Mary Martz and Christa in clothes by Betsey Johnson, Woolf Dummy Form Factory - New York City, 1975

Archival pigment print

© Estate of Deborah Turbeville

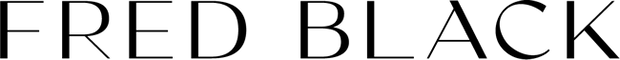

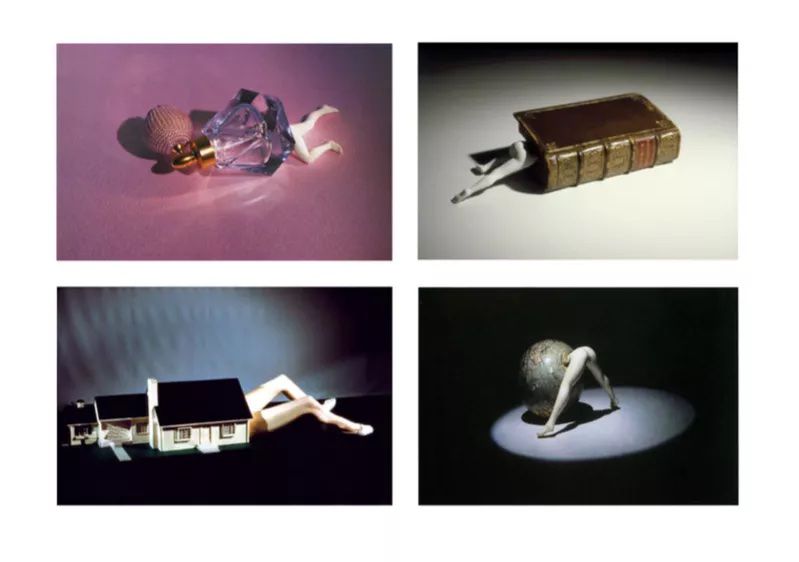

Laurie Simmons

Lying Objects, 1992

Offset prints

© Laurie Simmons

ARTWORK INFORMATION

Marilyn Minter juxtaposes photorealistic paintings with painterly photographs, homing in on the moment where clarity becomes abstraction and beauty meets the grotesque. Through painting, photography, and video, she has created a vast body of work which focuses on the female body and its portrayal in art history and popular media.

Minter often captures her subjects through panes of wet or steamed glass, commenting on the voyeuristic relationship between artist and muse, once the domain of a male-dominated Western art historical canon, Minter’s bathers and figures express their own agency. Drip Drop (2018) offers an extreme close up of a model’s lips, lacquered with metallic make up, slick and shimmering with shower condensation and sweat. Minter’s subjects flaunt their bodies, and luscious lips, her bathers face the viewer directly. The artist’s palette is hyper-vivid, and the blurriness caused by the glass that she photographed these ladies through render her subjects as impossible fantasies.

On a late June afternoon in 1962, Marilyn Monroe arrived at the Hotel Bel-Air in Los Angeles — Vogue had assigned Bert Stern to photograph the actress, and during the 12-hour session she posed nude, wrapped in sheets or draped in pearls, diaphanous scarves, and paper flowers. Legend has it Stern's first words to Monroe were, "You're beautiful," and she replied, "What a nice thing to say."

Vogue was so pleased with the initial images they sent him back for an additional two days of shooting. The following two sessions, yielded nothing short of magic; the series of 2,571 portraits revealed a Marilyn both shockingly unvarnished and utterly glamorous in wispy scarves, pink silk, birdcage veils, and an iconic black velour evening gown by Christian Dior. Collectively called The Last Sitting, the intimate portraits would be the public’s final glimpse into the life of the Hollywood icon before her untimely death six weeks later.

Bert Stern went on to publish the full series of portraits in 1982 –– The Last Sitting includes the complete series of finished portraits, contact sheets, shots that didn’t make the cut. The publication is a unique insight into Stern’s process, and most remarkably includes selections and edits by Marilyn herself. In Marilyn Double X, 1962 we can see the image had been rejected by Monroe, the contact sheet has been marked with a double cross, and the surface scratched with her hairpin. The contact sheet selections, and Marilyn’s rejections, offer us a glimpse into the photographer’s process, and the intimate collaboration between artist and subject.

Daniel Cherbuin (b. 1971) lives and works in Zürich, Switzerland and has long inhabited the intersection of alternative pop art and the underground music scene with his video art, montages and assemblages. Cherbuin’s video art converts music into clips and visuals in ingenious ways, collaborating with bands and delving into experimental film.

Tetrapak (2022) seen at Fred Black in Miami Beach, is an extension of Cherbuin’s playful and irreverent experiments in video art. Appropriating fashion photography from the 70’s, the artist brings the models to life with animated eyes. Humorous, seductive, and unsettling – the blinking, winking and wandering eyes capture the viewer’s attention and reverse the gaze.

Fashion takes itself more seriously than I do

– Deborah Turbeville

In the world of 1970s fashion, when images that highly sexualized women were de rigeur, Deborah Turbeville entered with an anti-fashion sensibility. Instead of suggestive shots of sexy women in gorgeous clothes, Turbeville’s work was almost always in black and white, atmospheric, theatrical, and more than a little dark. For the viewer, the net effect of Turbeville’s work is one of dreamlike, melancholy beauty. Her images exude an almost palpable sense of longing, with questions about the woeful women they depict — Who are they? Why are they so sad? — hanging unanswered in the air.

I wanted to make pictures that were psychological, political,

subversive. Images from my subconscious that could inform.

–– Laurie Simmons

A central figure of the Pictures Generation, Laurie Simmons (b. 1949) is a photographer and filmmaker who imbues her subjects (primarily dolls, puppets, and other inanimate human-like entities) with living energy, suffusing synthetic spaces with nostalgia colored by an adult’s memories, longing, and regret. Simmons’s work blends psychological, political, and conceptual approaches to artmaking transforming photography’s propensity to objectify people, especially women, into a sustained critique of the medium. Mining childhood memories and media constructions of gender roles, her photographs are charged with an eerie, dreamlike quality. At first glance, her works often appear whimsical, but there is a disquieting aspect to Simmons’s child’s play, as her characters struggle over identity in an environment in which the value placed on consumption, designer objects, and domestic space is inflated to absurd proportions.

In Lying Objects 1992, the artist used a collection of legs, including those from human scale to miniature models, arranged below recognizable domestic objects such as cakes and musical instruments. The pieces become personified, emphasizing the ways in which the media circumscribes and fetishizes the human figure, particularly that of women.